SEC PROBES BIG BROADWAY FUND'S 'OUTSIZED' RETURNS (EXCLUSIVE)

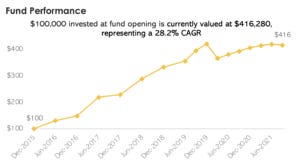

By their own account, the founders of the Broadway Strategic Return Fund turned an overlooked investment niche into a bonanza. Hunter Arnold, John Joseph and Curt Cronin established their hedge fund in January 2016 to invest in U.S. and U.K. live theater productions, plus tours, cast recordings and other ancillary businesses. With "few professional investors participating through a highly organized and disciplined investment process," the fund's Sept. 30, 2021 Due Diligence Questionnaire said, the founders believe "there is an untapped opportunity for outsized profits." The year-old marketing document declared, "$100,000 invested at [the] fund opening is currently valued at $416,280." That's double the rate of return of the Standard & Poor's 500 Index over the same period -- a remarkable result for an industry in which roughly 80 percent of commercial theater productions fail to fully repay their investors, let alone turn a profit.

Broadway Strategic Return Fund's investment performance, including the compound annual growth rate, from a tear sheet filed in court.

John Joseph

On Sept. 1, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission announced that it's scrutinizing the figures. For nearly three years, the Federal agency said it's been investigating whether Joseph and Cronin or others "materially overstated the Fund’s valuation or performance to prospective or actual investors," according to a filing in Federal court in Manhattan. The SEC has demanded documents and communications concerning how the fund calculates investment returns and how it forecasts future results to value its holdings. The SEC said it's also looking into whether the fund’s questionnaires misrepresented the existence of the ongoing investigation.

The SEC publicly disclosed the inquiry in a lawsuit against Joseph and Cronin to compel them to comply with outstanding subpoenas. Joseph is a consultant and futures trader who oversees the fund's legal, compliance and finance operations; Cronin's a consultant and retired Navy SEAL who runs administration, operations and marketing. Arnold, one of Broadway's busiest producers, isn't named in the SEC complaint.

The agency said that it hasn't concluded whether securities law violations occurred. Ernest Badway of Fox Rothschild LLP wrote in a Sept. 12 court filing that after receiving more than 850,000 pages of documents, "the SEC has not pointed out a single flaw in the Fund’s valuation methodology, nor has the SEC charged my clients [Cronin and Joseph] with any wrongdoing arising out of their valuation methodology." Badway, who at the time was the fund's outside counsel, wrote that the questionnaires -- including one dated Dec. 31, 2020 -- were "completed accurately and truthfully."

The fund has been a significant source of capital for the industry as it struggles with canceled performances, inflated operating expenses, subpar attendance and a generally slow comeback from the pandemic. The fund raised $81.6 million from investors, it said in an August filing with the SEC. As of March, there was about $145 million committed to its investment strategy, according to a press release from the TASC group, a New York PR firm representing the fund. (The sum apparently includes at least one separately managed account.) The fund had stakes in 124 productions worldwide, the release said.

Hunter Arnold Arnold was a credited producer of a dozen Broadway shows last season and ten so far this season, starting with The Kite Runner and Into the Woods. Arnold's company TBD Theatricals is an "affiliated production company" that's "integrated with the fund and its investment activities," the questionnaires said. The fund, which doesn't back all of Arnold's shows, also lends money to productions, secured by the year-old New York City Musical and Theatrical Production Tax Credit. Joseph, Cronin and Arnold own Ridgeline Productions, the general partner of the fund. They declined requests for an on-the-record interview. This story is primarily based on hundreds of pages of documents filed in court. An SEC spokesman said the agency doesn't comment beyond public filings. The fund appears to be the largest of about a dozen theater-focused investment vehicles, which offer more diversification and theoretically less risk than backing a single production, said Townsend Teague, an industry consultant and entrepreneur. The fund charges a management fee of 2 percent of capital contributed and the principals retain what they earn for being co-producers of shows that the fund seeds. Investors are locked in for three years before they can take money out.

Curt Cronin When evaluating investments, the fund aims "not to select winners, but to identify and exclude opportunities with little or no chance of generating an acceptable risk-adjusted return," it said in the questionnaires. The general partner believes that its "proprietary data on show types, lead producer track records, creative team member success rates, and more help...significantly mitigate the Fund's risk and improve the Fund's potential for outsized gains." Underpinning its approach is the contention that "the theatrical business as a whole tends to be deceptively consistent and attractively profitable." The questionnaires don't provide many hard numbers to support this view, beyond its own results. The fund has disclosed stakes in hits (including Dear Evan Hansen and Hadestown ) and flops (Gettin' the Band Back Together, the 2017 revival of M. Butterfly). A fund balance sheet dated June 30, 2020 said its investments in shows and other ventures were acquired for $17 million and valued at $24.8 million. The balance sheet doesn't disclose when the investments were made. The purported 300 percent-plus total return and 28 percent compound annual growth rate described in the questionnaires and a promotional tear sheet may have involved a relatively small sum. The fund said it raised just $800,000 in 2016 vs. $10 million in 2020 and $12 million in the first nine months of 2021. Three small broker-dealers have "distribution agreements" with the general partner and earned commissions for securing clients. They are Castle Hill Capital Partners, of New York; Pickwick Capital Partners, of White Plains, N.Y.; and Uhlmann Price Securities, of Chicago, according to an SEC filing. Unlike the typical theater fund, which backs a prescribed number of shows and repays investors from profit distributions, the 'evergreen' Broadway Strategic Return Fund said it reinvests distributions and doesn't plan to make payouts until it's near "capacity" -- $500 million under management. How the fund gets valued takes up several pages of the questionnaires and is described as a collaboration between the general partner and a "valuation agent," Southlake, Texas-based ValueScope Inc., among others. The process involves projecting future cash flows for each holding, using past performance of comparable shows as a guide. In response to the March 2020 Broadway shutdown, a "probability-weighted, scenario-based overlay to our traditional valuation model" was added. (In contrast, the word ‘valuation' doesn’t appear in the 2018 operating agreement for the Araca Productions Fund II LLC, a more traditional $1.3 million offering that planned to seed about a dozen shows.)

SEC

The SEC said in an educational bulletin, which doesn't mention the Broadway Strategic Return Fund: "many hedge funds give themselves significant discretion in valuing illiquid [not easily traded] securities." And hedge funds need not follow a standard methodology when calculating performance. "Not following standard methodology is not the same as gross distortion," said Adam C. Pritchard, a professor at the University of Michigan Law School and coauthor of Securities Regulation: Cases and Analysis, in an email. "If the valuation is completely unreasonable, the SEC will pursue it." The SEC hasn't disclosed the catalyst for its probe. But in a letter to the agency, Badway, the fund's outside counsel, wrote: "We understand the Staff began this investigation as a result of a complaint filed by [the fund's] former auditor, Berkower LLC." In a filing, the SEC referenced "the Fund’s dispute with its former auditor regarding the valuation of the Fund’s assets." Badway claimed that the fund had a dispute with the Iselin, New Jersey-based auditor over a bill. And the lawyer filed a Jan. 15, 2020 letter in court from Berkower praising the fund's financial statement disclosures as "neutral, consistent and clear" and saying it encountered "no significant difficulties in performing and completing our audit." Badway omitted the financial statements and footnotes in his filing. Maurice Berkower, the managing principal of the auditing firm, declined to comment. On Jan. 31, 2020, the SEC issued a formal order of investigation directing staffers to take testimony and issue subpoenas In the Matter of Broadway Strategic Return Fund, LP, according to court papers. The fund and its leaders initially cooperated with the nonpublic probe, and in August 2021 turned over hundreds of thousands of pages of documents. SEC lawyers fixated on Q&As in the questionnaires denying the existence of an investigation. In telephone calls with Badway, SEC staff "expressed its concerns about the apparent falsity" of the marketing documents. The fund said in the questionnaires: "No, there [have] never been any investigations by an industry regulatory body of the Firm, its affiliated entities and/or any of its current or former Team Members,". Regarding current investigations, "There are no pending or ongoing litigation/investigation (sic) against the Firm, its affiliated entities and/or its current or former Team Members."

No Targets

In court papers, Badway noted that the denials refer to the "Firm" -- Ridgeline Productions, the fund's general partner -- not the fund itself. Moreover, the questionnaires didn't "specifically inquire as to a confidential, non-public SEC inquiry." And unlike a Grand Jury, "the SEC investigative process does not have targets," Badway wrote, citing the SEC's Enforcement Manual. Hence, "there was no pending litigation or investigation against the Firm (or the Fund)." While "the Fund and its Principals have been ruthlessly targeted because the arts as a business is simply something the SEC does not understand," Badway wrote, the agency never "indicated that anyone or entity was under investigation, relying upon its long-standing refrain of having no targets or subjects." (Italics added.) Badway cited case law that SEC investigations don't trigger disclosure obligations for public companies. SEC lawyer Victor Suthammanont rejected the comparison as not applying to the fund questionnaires, which were sent to prospective investors the SEC didn't identify. "This was, in fact, an affirmative question from a potential investor who, reading that question, asks 'Is the firm or any of its affiliates being investigated?'" Suthammanont said at a Sept. 14 hearing. "And the answer was 'no,' even though they knew of the investigation. And I think that that very well could be a securities law violation if the other elements are met." "Silence is golden," in regard to disclosure, Professor Pritchard said. "Knowingly misrepresenting is fraud." This past June, after extensive back and forth, Badway wrote to the SEC that Cronin and Joseph "will not be providing any further information to the Staff at this time." If the fund sought to keep the inquiry and its business dealings private, not complying with the subpoenas backfired. The SEC filed fund documents in court, several marked confidential, as part of its suit to enforce the subpoenas. During a July 2021 SEC hearing, Badway referenced a "Bain Capital transaction," according to a transcript excerpt filed in court. Asked to elaborate, Arnold said in a Sept. 9 email to Broadway Journal that Bain Capital, the private equity and venture capital giant, invested in a separately managed account "using the same methodology as our main fund." Arnold declined to say the amount, citing a non-disclosure agreement. A Bain spokesman declined requests for comment. In a March 2022 letter to the SEC, Badway wrote that the fund didn't "disclose the investigation to Bain based on its understanding that it was not required to do so for nearly a year." Badway added that the fund "had not informed anyone of the SEC investigation." On Sept. 14, at a brief hearing in lower Manhattan, Judge Jesse Furman ruled in the SEC's favor in the lawsuit and ordered Cronin and Joseph to comply with the most recent subpoenas and testify in the probe, Cronin for a second time. "I find that this is not even a close call," Furman said. On Sept. 28, Cronin and Joseph replaced Badway with two partners from the law firm Jenner & Block, one previously with the SEC's enforcement division, the other a former federal prosecutor. The new legal team wrote to the judge that they plan to cooperate with the investigation and turn over all requested documents by Nov. 14, per an agreement with the SEC. On Sept. 29, the legal case to compel compliance with the subpoenas was closed. The SEC's investigation is ongoing. Note: On March 6, 2023, five months after this story was published, a lawyer representing the fund received word from the SEC that it closed the investigation. Broadway Journal obtained the email via a Freedom of Information Law request. "We have concluded the investigation as to Broadway Strategic Return Fund, LP, (“Broadway Strategic”)," wrote the SEC official, whose name was redacted. "Based on the information we have as of this date, we do not intend to recommend an enforcement action by the Commission against Broadway Strategic. We are providing this notice under the guidelines set out in the final paragraph of Securities Act Release No. 5310, which states in part that the notice 'must in no way be construed as indicating that the party has been exonerated or that no action may ultimately result from the staff’s investigation.' (The full text of Release No. 5310 can be found at: http://www.sec.gov/divisions/enforce/wells-release.pdf.)"